Acts as context for the early church and Paul’s letters.

The Book of Acts provides important context for understanding the early church and the missionary activity of the Apostle Paul. Luke begins Acts where the Gospel of Luke ends—with a resurrected Jesus teaching his disciples. In the subsequent chapters Luke describes the pouring out of the Spirit and the expansion of the early church throughout the Mediterranean region. The apostle Paul plays a key role in this expansion through a series of missionary journeys, which are described in the second half of Acts. During these journeys Paul starts new churches in cities like Corinth, Philippi, and Thessalonica–churches that he later writes letters to. These letters make up a large portion of the New Testament, and Acts provides the context for many of these letters. While it is difficult to synchronize exactly the descriptions in Acts with Paul’s letters, Acts provides a general timeline for the early church and many of the NT writings.

From the events in Acts, we can arrive at a general timeline for the early church and the apostle Paul. However, there are two particularly debated issues that affect any more detailed timeline; those issues are: 1) Do the time periods mentioned in Galatians 1:18 (3 years) and 2:1 (14 years) overlap, or are they sequential (not to mention Gal 1:17 states Paul went to Arabia after his conversion, something Acts does not mention)? 2) Does Paul’s trip to Jerusalem, described in Galatians 2, match Acts 11:27-30 or Acts 15? With these issues in mind (as well as uncertainty whether Jesus was crucified in A.D. 30 or 33), here is a possible timeline (borrowed from Darrell Bock’s Acts commentary) for the early church based on Acts:

| Date | Event | Reference | Paul’s Letters |

| AD 33 | Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection | 4 Gospels; Acts 1 | |

| 50 days after resurrection | Pentecost and the pouring out of the Holy Spirit | Acts 2 | |

| AD 34 | Martyrdom of Stephen, scattering of the church from Jerusalem, Paul’s conversion | Acts 7-9 | |

| AD 48-49 | First missionary journey | Acts 13-14 | |

| AD 49/50 | Jerusalem Council | Acts 15:1-35 | Galatians (shortly before council) |

| AD 50-52 | Second Missionary Journey | Acts 15:36-18:22 | 1-2 Thessalonians |

| AD 53-57 | Third Missionary Journey | Acts 18:23-21:16 | 1-2 Corinthians, Romans |

| AD 57-59 | Paul’s arrest and imprisonment | Acts 21:27-26:31 | |

| AD 59-61 | Paul’s journey and imprisonment in Rome | Acts 27-28 | Philippians, Colossians, Ephesians, Philemon |

| AD 62-63 | Paul’s release from prison and trip to Spain | Romans 15:24, 28; 1 Clement 5:5–7 | 1 Timothy |

| AD 64-66 | Paul’s imprisonment and execution in Rome | 2 Timothy 1:8; 4:6–8: Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.22 | Titus, 2 Timothy |

Paul’s missionary activity is followed in a more detailed way throughout Acts. The following paragraphs summarize and follow Paul’s journeys in text and in maps.

First missionary journey.

Paul’s first missionary journey is described in Acts 13:1–14:28. The Holy Spirit calls the church in Antioch to “set apart for me Barnabas and Saul for the work to which I have called them.” After fasting and prayer, the church sends out Paul and Barnabas (who also take along John Mark). The journey followed the following route:

After leaving Antioch (Acts 13:1–3), they travel to Seleucia (Acts 13:4) to Salamis (Acts 13:5) to New Paphos (Acts 13:6–12) to Perga of Pamphylia (Acts 13:13; John Mark leaves the mission) to Antioch of Pisidia (Acts 13:14–52) to Iconium (Acts 14:1–7) to Lystra (Acts 14:8–20) to Derbe (Acts 14:20). After Derbe, Paul and Barnabas double back to visit the same towns again and appoint elders in Lystra, Iconium, and Pisidian Antioch (Acts 14:21–23). They then travel to Perga and Attalia (Acts 14:25) and finally back to Antioch (Acts 14:26–28).

________________________________________________

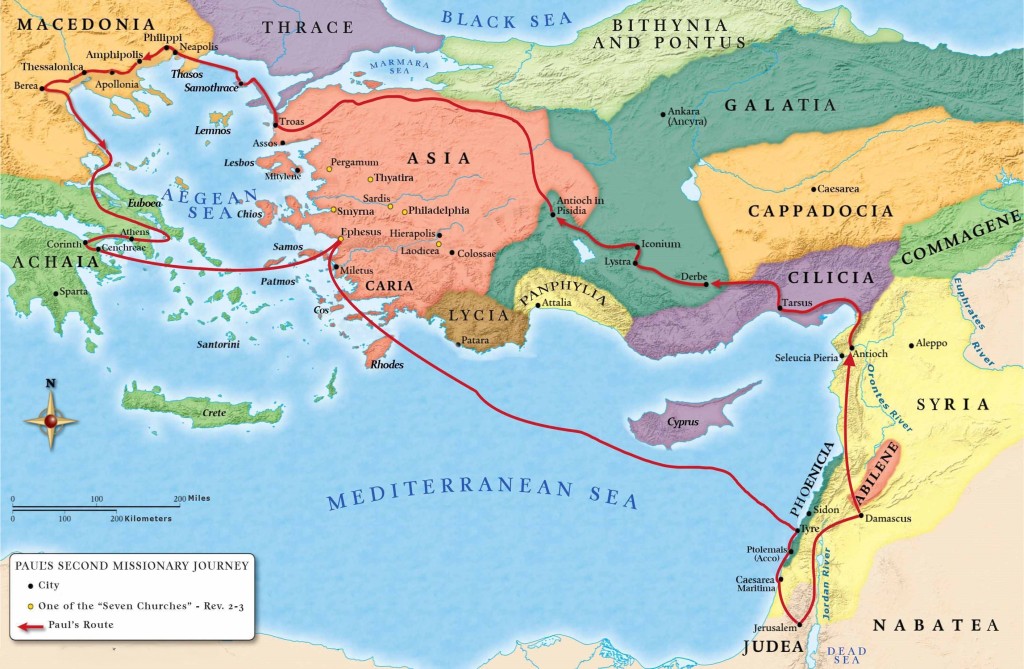

Second missionary journey.

Paul’s second missionary journey is recorded in Acts 15:36–18:22. Shortly after the Jerusalem council, Paul and Barnabas decide to return and visit the churches in every city where they had proclaimed the word of the Lord (Acts 15:36). Paul and Barnabas sharply disagree over taking John Mark with them again to the point that they part ways; Paul instead takes Silas with him, and Barnabas sails for Cyprus with John Mark.

Some of Paul’s most memorable encounters happen on this journey. In Lystra, Paul meets Timothy and invites him to join his missionary team (Acts 16:1-3). Timothy would be one of Paul’s most trusted fellow-workers (Rom 16:21; 1 Cor 4:17; Phil 1:1; Col 1:1; 1 Thes 1:1; Philemon 1:1; 1-2 Timothy). Passing through Asia to Troas, Paul receives a vision of a man from Macedonia calling him to cross the Aegean sea. Soon after, Paul and his companions set sail for the Macedonian region (Acts 16:8-10). In Philippi, Paul casts a fortune telling spirit out of a slave girl, which enrages her masters to the point they get Paul and Silas put in jail (Acts 16:16-24). An earthquake from the Lord frees Paul and Silas who choose to witness to the jailer rather than flee (Acts 16:25-40). After further travel, Paul eventually arrives in the Greek city of Corinth and spends about a year a half there. Paul most likely wrote his two letters to the church of Thessalonica during this stay at Corinth. Paul also meets Priscilla and Aquila, who become a trusted ministry couple for years to come (Acts 18:18-26; Rom 16:3; 1 Cor 16:19; 2 Tim 14:9).

The second missionary journey went along the following route: After leaving Antioch, Paul and Silas travel to Syria and Cilicia (Acts 15:41) to Derbe and Lystra (Acts 16:1–5) through the Phyrgian and Galatian region (Acts 16:6) to Mysia (Acts 16:7–8) to Troas (Acts 16:8–10). By boat they went to Samothrace (Acts 16:11) and on to Neapolis (Acts 16:11). Once again on land, they travelled to Philippi (Acts 16:12–40; 1 Thess 2:2; Phil 4:15). They then went through Amphipolis and Apollonia (Acts 17:1) on the way to Thessalonica (Acts 17:1–9; 1 Thess 2:1–10; Phil 4:16) to Berea (Acts 17:10–14) to Athens (Acts 17:15–34; 1 Thess 3:1–6) to Corinth (Acts 18:1–17; 1 Cor 3:6). Paul then headed back by boarding a ship at Cenchrea (Acts 18:18) and sailed to Ephesus where he left Priscilla and Aquila (Acts 18:19–21) and then sailed on to Caesarea (Acts 18:22). From Caesarea, Paul and Silas probably went to Jerusalem before eventually returning to the church in Antioch.

__________________________________________________

Third missionary journey

Acts 18:23–21:16 describes Paul’s third missionary journey, which once again departs from Antioch. After encouraging the churches in Galatia and Phyrgia, Paul arrived in Ephesus, where he successfully ministered for about three years (Acts 19). Threats and violence from those who made idols of the goddess Artemis caused Paul to finally leave. During his stay in Ephesus, Paul most likely wrote his first letter to the Corinthians, and sometime later his second letter to the Corinthians in response to a report from Titus (2 Cor 7:6, 13; 8:16-23). From Ephesus, Paul visited Macedonia and went on to Greece. Paul stayed three months in Greece, mostly likely in Corinth the majority of the time where he wrote the epistle to the Romans. On the return trip to Jerusalem, Paul went through Macedonia again, visiting Philippi. After sailing from Troas to Miletus, the elders of the Ephesian church met with Paul for the last time (Acts 20:17-38). From there, Paul and his companions traveled to Caesarea by boat, making several stops along the way (Acts 21:1-8). After a short stay in Caesarea, Paul and others made the pilgrimage to Jerusalem for the feast of Pentecost and for Paul to fulfill his oath (Acts 21:15-26).

We can trace the third missionary journey through the following places: Paul and his companions went through Galatia and Phyrgia strengthening disciples (Acts 18:23) and on to Ephesus, where Paul stayed 3 years (Acts 19:1–40; 1 Cor 16:8). After the stay in Ephesus, they went through Macedonia strengthening the churches on their way to Corinth/Greece (Acts 20:2), where they stayed 3 months. As they headed back to Syria/Jerusalem they once again passed through Macedonia/Philippi (Acts 20:3–6a). From Philippi they sailed to Troas where Paul raised the boy who fell out a window (Acts 20:6b–12). They then sailed to Assos, Mitylene, Chios, Samos (Acts 20:13–15) and on to Miletus (Acts 20:16–38). After meeting with the Ephesian elders in Miletus, they sailed to Cos, Rhodes, Patara (Acts 21:1–2) and on to Tyre (Acts 21:3) to Ptolemais (Acts 21:7) to Caesarea (Acts 21:8–14) and finally to Jerusalem (Acts 21:15, 17–26).

______________________________________________________

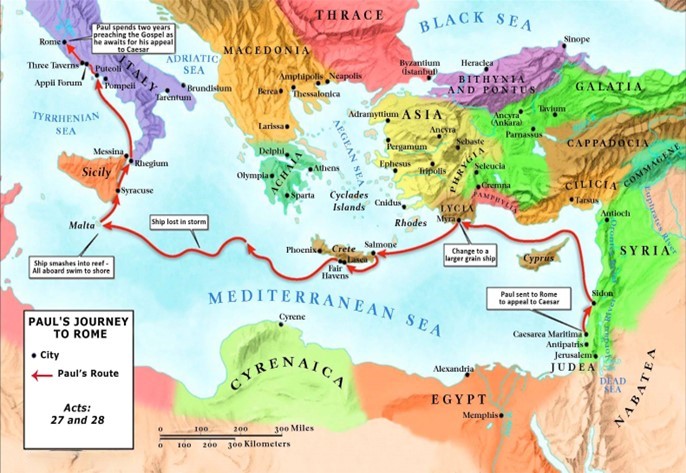

Journey to Rome

After his arrest for causing a disturbance in the temple, Paul remains in custody for at least two years awaiting trial. During this time, the Jewish leaders accuse and plot to kill Paul, and Paul makes several speeches and appeals before various Roman authorities (Acts 22:22-26:31). All these Roman authorities appear to consider Paul innocent, which may be the author’s way of showing Christianity’s harmlessness to Rome and its citizens. After appealing to Caesar during his trial before the governor Festus (Acts 25:11-12), Paul begins his journey to Rome. The mostly ocean voyage takes several months due to a shipwreck on the island of Malta. After finally arriving in Rome, Acts 28:30-31 states that Paul proclaimed the gospel without hindrance for two years as he awaited trial. The book of Acts ends with this statement of Paul’s bold proclamation of the gospel in Rome, which was a fitting fulfillment of Jesus’ commission (Acts 1:8) to be his witnesses to “the ends of the earth.” From his letter to the Philippians, we learn that Paul even had opportunity to spread the gospel among the imperial guards, and to Caesar’s household (Phil. 1:12-13; 4:22). In addition to his epistles to the Philippians, Paul also probably wrote his epistle to the Colossians, Ephesians, and to Philemon during his Roman imprisonment.

Very early tradition suggests that Paul was released after this imprisonment (1 Clement 5:5–7; Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.22) and continued even further west on another missionary journey. During this period of freedom, Paul probably wrote First Timothy and Titus. Not long after his release, Emperor Nero blamed the great Roman fire on Christians. A severe persecution broke out against the Christians, which probably resulted in Paul’s re-arrest and transfer to Rome. During this imprisonment Paul wrote his last letter—Second Timothy. Paul was most likely martyred by Nero sometime in AD 64-66.

___________________________________

End Notes

Bock, Darrell. Acts. BECNT; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2007.

Lenski, R. The Interpretation of the Acts of the Apostles. Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1961.

Parsons, M. Acts. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008.

Schreiner, Patrick. Acts. Christian Standard Commentary. Holman Publishing, 2021.

Simeon’s Story: An exegetical retelling of Luke 2:25-39.

Preachers often assume that an exegetical presentation of a text requires the typical sermon format. However, one can present the meaning of a text, along with its historical and literary context, in other formats. Below is an example of an one person exegetical drama from the perspective of Simeon. You will notice that a lot of historical context is woven into Simeon’s speech as well as references to the most likely Old Testament allusions. Care was also taken to emphasize Luke’s most likely purpose in including the Simeon pericope in his Gospel.

The hermeneutical task includes presenting a text in a way that hearers can understand and apply. Certain hearers are better able to hear and apply a first-person presentation of an exegeted text. When preachers vary their presentation, they are more likely to reach a broader spectrum of listeners. I hope you find the following presentation of Luke 2:25-39 helpful to your preaching.

Simeon’s story. A historically based, first-person retelling of Luke 2:25-39

As I look back on my life, I see it has been a life of waiting. Even as a child, my father and I would scan the western horizon for clouds as we waited for the spring rains to refresh the land. He would say, “Simeon, don’t let the wait for rain dampen your spirits.” He told me that every new generation of Israelites must learn to wait on God. Our God announces something through his prophets, and it might take centuries for God’s promises to be fulfilled-but our God keeps His promises. Our ancestors waited in Egypt for 400 years before God raised up Moses to deliver them from slavery. My father assured me that one day God would send a savior whose kingdom will never end. He said, “The prophets have predicted it, so we can count on it. Until then we wait for God’s kingdom, and we don’t settle for a man-made substitute.”

I later understood that my father was speaking about the Jewish Hasmonaeans who claimed to be God’s chosen rulers. When I was a boy, Israel was actually independent. After the Maccabean revolt threw off foreign rule, many thought that the prophecies of restoration were fulfilled and the wait for Israel’s golden age was over. But eventually the Jewish kings were not much better than foreign ones, and infighting caused them to invite the Romans to come help. The problem is when the Romans help, they help themselves to whatever is best for Rome. When I was a young man just starting on my own, the Romans marched into Jerusalem. We are still waiting for them to leave.

I later understood that my father was speaking about the Jewish Hasmonaeans who claimed to be God’s chosen rulers. When I was a boy, Israel was actually independent. After the Maccabean revolt threw off foreign rule, many thought that the prophecies of restoration were fulfilled and the wait for Israel’s golden age was over. But eventually the Jewish kings were not much better than foreign ones, and infighting caused them to invite the Romans to come help. The problem is when the Romans help, they help themselves to whatever is best for Rome. When I was a young man just starting on my own, the Romans marched into Jerusalem. We are still waiting for them to leave.

After years of Roman occupation my cousin got tired of waiting. He joined a group of zealots that planned to take Israel’s salvation into their own hands. The Romans heard about the group and crucified them all before they even had a chance to raise their swords in battle. No, only God can bring lasting deliverance. Decade after decade I prayed that God would send the promised Messiah to shine His glory throughout the world and to restore our land. Of course, there were many pretenders who tempted us to think our wait was over – for instance the current king, Herod. He convinced the Romans to install him as our local “Jewish” king (Herod is from Idumea not Israel). Herod craftily pitches himself as a new Solomon. He is re-building the Jerusalem temple so that it is even bigger than Solomon’s. Herod wants people to think he is some sort of savior, but he only uses our faith to get popular support. Herod is just another human pretender – a self-obsessed Roman puppet that will cling to power at all costs. Men like Herod made me long for God to fulfill His promises even more.

All my life I waited for God to send a savior as the prophets foretold. I was not just praying for an end to political pain, but personal pain. I have outlived so many of my family members, even some of my grandchildren. My family and I have suffered from drought, hunger, theft, violence, and death. Countless nights I have prayed Psalm 13, “How long, oh Lord will you forget us forever.” My lament was not because I didn’t believe, but because I knew God as gracious and merciful, slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love. I trusted in the promises He made, so I continually and fervently prayed. Decade after decade I waited faithfully, following what I knew God wanted in my life each day. Faith is not just knowing the prophecies but acting right every day. In my daily life I sought to love my neighbor, to give to those in need, and to point people to God. Every day I tried to live faithfully and expectantly in the waiting. 10 years turned to 20, 20 turned to 30, 30 turned to 40.

Finally, God spoke! The Lord revealed that I would not die until I saw the Lord’s anointed! How did he speak? I didn’t hear an audible voice, but as I read through Isaiah’s prophecies of redemption, the Spirit filled me with a conviction that I would see this Messiah with my own eyes! I had a renewed purpose. I was to be a watchman who waits for this King so that I can announce His arrival! I constantly told people that He was coming soon. I continued praying that I would remain watchful and in God’s will. The Spirit of the Lord was upon me. Yet many more months passed and the Lord’s anointed still didn’t arrive. I experienced more heartaches and more injustice from worldly rulers. I prayed as I had for many years, but with an increased urgency: “Lord, how long? I am getting so old; my body is wearing down. More loved ones have died. How much longer? Nevertheless, I trust you, Lord.” More waiting.

Then last week, the Savior arrived! The Spirit impressed upon me to go to the temple immediately. I went as quickly as these old bones would take me, but I felt a renewed strength as if I was soaring on the wings of eagles (and I certainly was sore the next day). I waited at the gates of the temple, scanning the crowds of worshippers. I prayed that the same Spirit who directed me there would direct me to the right couple.

I noticed a rather plain looking couple carrying an infant. The father had 2 turtledoves- the offering for purification after childbirth that Moses directed in Leviticus. Leviticus actually called for an offering of a lamb and a turtledove. However, the poor could substitute another turtledove for the lamb. The woman looked so young, still in her teens. Just as my eyes were about to move on from this plain, poor couple, I was overwhelmed with the Spirit. This was the one I had been waiting for! I called to the couple, “Wait, let me see your child!” The couple was somewhat startled, but the young woman tilted the infant towards me and said, “This is Jesus. We have come to dedicate him to the Lord our God and give the purification offering.” His name was Jesus, which means “Yahweh saves”! Here was the savior, and the salvation, we had waited for. The prophecy and my purpose were fulfilled. I said to the couple, “Let me bless this child!” I took this child in my arms and said: “Lord, now you are letting your servant depart in peace according to your word; for my eyes have seen your salvation that you have prepared in the presence of all peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and for glory to your people Israel.”

My mind was overflowing with Isaiah the prophet’s words, which were being fulfilled right in front of me! Almost any scripture from the last third of the scroll seemed relevant to the moment, but one that I have written to keep by my heart is this: “The voice of your watchmen—they lift up their voice; together they sing for joy; for eye to eye they see the return of the Lord to Zion. Break forth together into singing, you waste places of Jerusalem, for the Lord has comforted his people; he has redeemed Jerusalem. The Lord has bared his holy arm before the eyes of all the nations, and all the ends of the earth shall see the salvation of our God” (Isaiah 52:8-10). It was not just the prophetic words of Isaiah that were being fulfilled, but the Lord’s personal word to me that I would not die until I saw the Lord’s Christ.

One day this child will set the captives free, restore sight to the blind, and invite people to repent and enter God’s kingdom! This invitation will not just be to my people; the Messiah will be a light to all nations. Indeed, the Lord God promised our father Abraham that all the nations would be blessed through his descendants. We children of Abraham were not only meant to share in God’s glory ourselves but share it with the nations. Although we have failed at that task many times, the Lord himself is seeing His plan through. This child will bring the light of God to the world and restore the glory of God to Israel. Joy to the world, the Lord has come!

Mary and Joseph marveled, and I pronounced a blessing upon them as well. As I handed the child back to his mother I looked into her eyes (such strong eyes for such a young women) and even more prophetic scriptures flooded my mind. The Lord’s Messiah will bring salvation and restoration, but true restoration requires removing that which is against God. Isaiah spoke of the Messiah as a suffering servant who would take on sin. As this servant takes on that which is against God, he would suffer rejection and even death. This young woman would experience not just the joy of God working through her son, but the sorrow from those who will oppose Him. The prophetic words came out of my mouth before I even realized it: “Behold, this child is appointed for the fall and rising of many in Israel, and for a sign that is opposed (and a sword will pierce through your own soul also), so that thoughts from many hearts may be revealed.”

Just as salvation is centered on this child, this child himself would be the decision point that reveals people’s hearts towards God. God’s purposes will not be universally supported; they will also be opposed. Mary’s son will be the corner stone of God’s kingdom that some builders will reject. My people have a long history of rejecting God’s covenant gifts, and it will be no different in the messianic age. Conflict will arise that will not only expose the hearts of people, it will pierce the heart of this strong, but young mother.

My somber realization was quickly overshadowed by the arrival of Anna, the daughter of Phanuel of the tribe of Asher-a prophetess. Since before Herod even started rebuilding the temple, Anna was a fixture in the temple courts, praying and fasting for the redemption of Jerusalem. When I first met Anna, I asked her about her frequent fasting. She said, “I am a weak widow with no worldly power. Fasting is a type of protest that something is not right. When I fast and pray, I am calling on the power of heaven to come and fix what is not right. I cannot save anyone from the injustice and pain of the world, but God can.” God heard Anna’s pleas, and He often spoke a prophetic word through Anna. Sometimes she would proclaim that God’s redemption was coming and call us to repentance. On that day, the Spirit spoke the same thing to Anna as He spoke to me – your wait is over. Anna joined me in giving thanks to God and witnessing “to all who were looking forward to the redemption of Jerusalem”. Anna and I were the 2 witnesses that God brought together that day to proclaim and celebrate that the wait for the Savior was over!

My somber realization was quickly overshadowed by the arrival of Anna, the daughter of Phanuel of the tribe of Asher-a prophetess. Since before Herod even started rebuilding the temple, Anna was a fixture in the temple courts, praying and fasting for the redemption of Jerusalem. When I first met Anna, I asked her about her frequent fasting. She said, “I am a weak widow with no worldly power. Fasting is a type of protest that something is not right. When I fast and pray, I am calling on the power of heaven to come and fix what is not right. I cannot save anyone from the injustice and pain of the world, but God can.” God heard Anna’s pleas, and He often spoke a prophetic word through Anna. Sometimes she would proclaim that God’s redemption was coming and call us to repentance. On that day, the Spirit spoke the same thing to Anna as He spoke to me – your wait is over. Anna joined me in giving thanks to God and witnessing “to all who were looking forward to the redemption of Jerusalem”. Anna and I were the 2 witnesses that God brought together that day to proclaim and celebrate that the wait for the Savior was over!

I don’t know exactly what will happen as this child grows. I do know he will expose the hearts of many. If Herod finds out, his jealous heart will seek this child’s life. Because of opposition, pain and conflict will continue for a time. While I won’t be around to see exactly what the next step will look like, this child is another reminder that God keeps His promises every step of the way. We can wait on him for the next step. Even if the wait has been long and full of sadness, God does what He says. His plan and purposes are bigger than my short life, even though He called me to be a part of His plan. Now I can depart this world and its troubles in peace, knowing that God’s plan and promises have prevailed and will prevail. Until the day I depart this earth, I will tell this story and invite all to receive this Jesus and God’s salvation. Is your heart open to receive this child? My heart and Anna’s heart are full of joy as we receive this savior, this king – our wait is finally over! With my last breath, this watchman can call out, “Joy to the world the Lord has come, let earth receive her king!”

Psalm 19, Encountering the Creator through A.W.E. of Creation

Since history began, creation has inspired a sense of AWE in people. The opportunities for awe are as varied as creation itself: a sunset, a mountain top vista, the birth of a baby, a honeybee in a colorful flower. As technology has developed, and we see to the microscopic level or deep into the universe, our awe has only increased! The Hubble and James Webb telescopes have brought us amazing images of far flung galaxies-each with billions of suns and planets. Microscopes have unlocked microscopic processes that have a fine-tuned accuracy and intricacy.

With amazing technology, we see farther and describe natural processes more accurately, but creation still stirs the same ancient feeling in humanity. That sense of awe brings with it deep questions and yearnings for the “why” and “who” behind it all. Awe of creation stirs in us a desire for the transcendent – the meaning and reason behind the universe. As Ecclesiastes 3:11 says, “God has made everything beautiful in its time. Also, he has put eternity into man’s heart.” Awe of creation is meant to stir our hearts to consider the awesome eternal creator of it all!

Many scriptures encourage us to consider various aspects of creation as a way to draw near to the Creator. Today we look at Psalm 19 not just as a beautiful song about creation and the creator, but as a guide on how to let the AWE of creation connect us to the awesome creator.

In Psalm 19 The Psalmist begins (1-6) by turning his attention to the sky and being awestruck at how it declares God’s glory. In this section the writer focuses on how God even controls the mighty sun, which runs across the sky like a strong man. Verse 7 shifts from general to special revelation as the writer extols God for His word. The psalmist finishes by Encountering God personally in verses 12-14 expressing a personal confession of repentance and a plea for God to help him see and overcome his own sinful struggles. The AWE of creation set the Psalmist on the path to deeper connection to the awesome creator. This psalm can also guide us so that those stirrings of awe in our heart at nature’s glory can draw us into an encounter with the creator of it all.

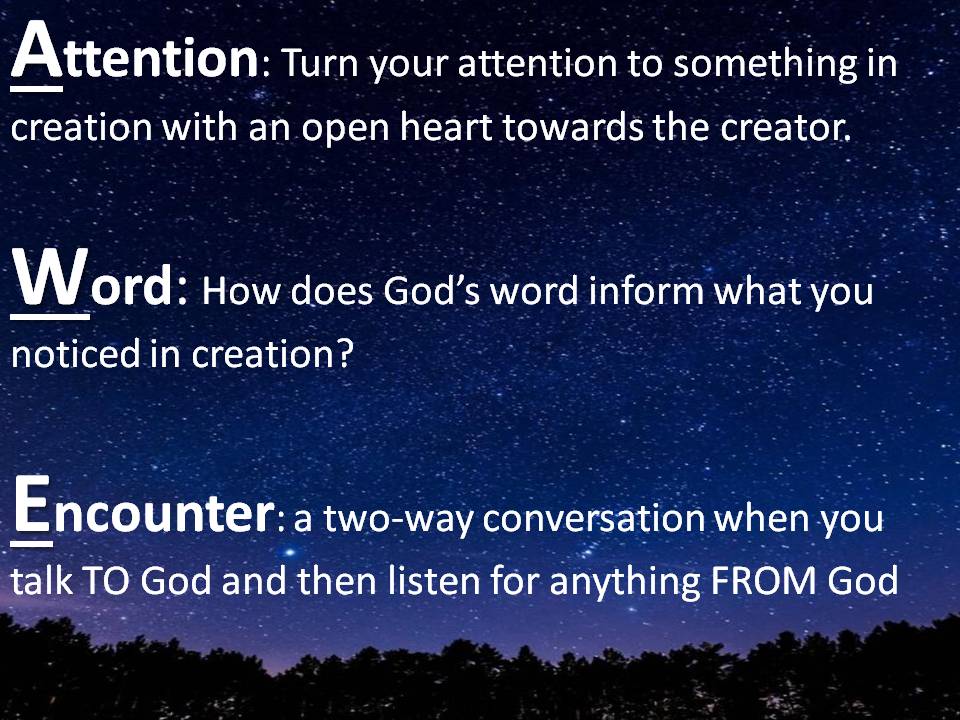

Psalm 19 and the acronym A.W.E. give us a simple method to connect with creation as a way of drawing close to the Creator.

Attention. Turn your attention to something in creation with an open heart toward the creator What feelings/thoughts does it stir up? What does this part of creation reveal about the creator?

Psalm 19: The heavens declare the glory of God, and the sky above proclaims his handiwork. 2 Day to day pours out speech, and night to night reveals knowledge. 3 There is no speech, nor are there words, whose voice is not heard. 4 Their voice goes out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world. In them he has set a tent for the sun, 5 which comes out like a bridegroom leaving his chamber, and, like a strong man, runs its course with joy. 6 Its rising is from the end of the heavens, and its circuit to the end of them, and there is nothing hidden from its heat.

The Psalmist turns his attention to the sky. In particular he focuses on the sun and how it charges across the sky. Nothing can escape the sun; “nothing is hidden from its heat.” If you have ever sat in the shade for a while, you know that what once was shady is sunny after a couple hours. How much more, therefore, can one not hide from the creator of that sun! The sky and sun proclaim God’s glory, it is His handiwork. Although it doesn’t proclaim it with words, the message of the creator of it all goes across the globe just like the sun. Verse 4: “Their voice goes out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world.” This is “general revelation”.

Command to pay attention or consider creation as a way to connect with the creator is all over scripture. Psalm 8 calls us to consider the night sky (astronomy), Psalm 139 proclaims the wonders of the human body (biology), and Jesus himself taught important truths by pointing to examples from creation.

While it is easy to be “blown away” with awe at the Grand Canyon or Niagara Falls, even the little things of creation can stir us if we would just pay attention. The crystals on the window from a cold winter’s night have a geometric beauty that can stir the soul.

Scripture commands us to pay attention to how the created order points to the glory of the creator. So step 1 in following Psalm 19 is to turn our attention and consider some part of creation. We can do this every day.

God’s word or message goes out in a general sense through creation (that is why creation is often referred to as “General Revelation”), but general revelation only reveals so much. For instance, if the sun is powerful and inescapable, how much more powerful is the creator! But many questions remain: Is that powerful God still active in the world? Does this God want to burn us? These questions require “special revelation” to answer. Special revelation is when God reveals his word or message in human language. Step 2 is considering God’s word, which the Psalmist turns to in 19:7-11.

7 The law of the LORD is perfect, reviving the soul; the testimony of the LORD is sure, making wise the simple; 8 the precepts of the LORD are right, rejoicing the heart; the commandment of the LORD is pure, enlightening the eyes; 9 the fear of the LORD is clean, enduring forever; the rules of the LORD are true, and righteous altogether. 10 More to be desired are they than gold, even much fine gold; sweeter also than honey and drippings of the honeycomb. 11 Moreover, by them is your servant warned; in keeping them there is great reward.

Word. Following Psalm 19’s pattern, the message of God’s creation pushes us to His revealed word. The Psalmist first considered creation, but then in 19:7 turned to how the word of God is also beautiful and so valuable in guiding a person into God’s will and blessings. God’s word gives us answers to those stirrings from creation: “This creator is more powerful than all these things beyond me, but is he knowable, is he loving? Why did he make it all?” God’s word, or special revelation, is where God reveals himself in human language so that He can be known.

Once we pay attention, how does God’s word (scripture) inform what you noticed in creation? It can be something concrete and direct, like noticing an eagle and that reminds you of Isaiah 40:31, “they who wait for the LORD shall mount up with wings like eagles . . .” Or noticing something that reminds you of a general biblical concept-like a fallen tree reminds you of mortality and that we will stand before God. Look at the created thing through the lens of God’s word.

The need for God’s word is crucial to both Jewish and Christian understanding. God has revealed himself, he has spoken to and through people. Just like God has put laws into nature, like gravity, like the speed of light, he has a moral law to guide and form us. As God’s image bearers, and moral agents, God reveals His will and ways to us.

When we think of “law” we think of constraints and reluctant obedience, but the Psalmist sees the law as beautiful, sweat as honey, and valuable like gold. Because the law (which is the Hebrew word Torah, which refers to all of God’s revelation) reveals who God is in an even more particular way, it is particularly valuable and beautiful. The bright morning sun speaks to the radiance of the God who made it, but God’s word reveals that this God is also abounding in love and wants to share his radiance with creation. So we interpret what we see through the lens of Word.

A side note on the term “God’s word” – Jesus is also referred to as the Word (John 1:1-4). Jesus is God’s ultimate self-revelation! Through Jesus God has not only communicated in human language, but human flesh. While we can know someone through their writings, we can now them even better through a personal relationship! That relationship is possible because God made himself known through Jesus. In Jesus Christ we have the perfect intermediary between our Creator God and created humanity.

Because God has revealed himself in his word to be a personal God, that awe can bring us to an Encounter. Psalm 19:12-14 concludes on this note of encounter: 12 Who can discern his errors? Declare me innocent from hidden faults. 13 Keep back your servant also from presumptuous sins; let them not have dominion over me! Then I shall be blameless, and innocent of great transgression. 14 Let the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable in your sight, O LORD, my rock and my redeemer.

Encounter God. The psalmist finishes by encountering God personally, entering into a conversation with God in verse 13. The writer expresses a personal confession of repentance and a plea for God to help him see and overcome his own sinful struggles. This encounter should be a two-way conversation when you talk TO God and then listen for anything FROM God.

To God: Lift up thanks or praise to God for the things He has created and that you are able to enjoy them. The scriptures are full of calls to praise God for His wonderful work. Psalm 148 calls on all of creation: sun, moon, the seas, animals, everything to praise their creator.

From God: What do you feel God is telling you today? Whatever you noticed, especially when it has prompted you to seek and exalt God, has become an opportunity for you TODAY. Remember considering the word is so important to discerning what God is saying. People often hear what they want to hear, so God’s written word is the standard by which we measure whatever we think God is saying today. Go from the transcendence of the creator to the intimacy of a personal God who speaks to His people. The psalmist, perhaps from contemplating the inescapability from the sun’s rays, knows that the creator’s light will expose sin in his life, even hidden sin that he can’t see on his own. So he humbly calls on God for help. He wants to be transformed so that his words and deeds are pleasing to the creator. The Psalmist has had a personal encounter with the creator, but he began his journey with turning his attention to consider creation’s testimony about the creator, then the testimony of the word, until the inner testimony of the Spirit applied these things to him personally.

Discussion questions:

Describe the last time you were filled with awe over creation?

What occupies your attention most of the day? When could you set aside time to pay attention to creation with a heart open to the creator?

How might incorporating the AWE method improve your prayer time? How might it create difficulties?

Do you see the importance of looking at creation through the lens of God’s word? What are potential dangers of neglecting the word in this process?

Practice it! Go and try the AWE method above. What do you feel God is telling you today?

The Book of Revelation’s Structure

In the midst of an earthquake and eclipse in the Northeast United States, I was preparing to teach the book of Revelation for a New Testament Survey course. My preparations put these unusual phenomenon in their proper perspective. For one, John’s Apocalypse describes world-wide, end of time, events. Despite what residents of the Northeast U.S. might think, we are not the center of the world or history – especially salvation history. Most Christians today live in the global South and Revelation doesn’t even mention the United States. Second, the book of Revelation is cyclical, so the signs of the end-times will be things that have happened before and will follow patterns of intensification. The tribulations, disasters, and signs that it describes are drawn from Old Testament imagery. Revelation looks forward AND backwards to encourage people in the present to persevere in their faith. We often get lost in the strange details of Revelation and miss out on the stabilizing sovereignty of God featured in the book’s storyline. For this reason, an overall structural outline of Revelation is both needed and helpful.

In my opinion, Craig Koester has developed one of the best graphic outlines of Revelation’s cyclical structure (Revelation and the End of All Things, Eerdmans, 2018, pg 42–43). Scholars can’t seem to agree on an outline that accounts for all of Revelation’s quirks, twists, and turns, but Koester’s graphic accounts for several features of Revelation. Koester explains, “An outline of the book looks like a spiral, with each loop consisting of a series of visions: seven messages to the churches (Rev. 1–3), seven seals (Rev. 4–7), seven trumpets (Rev. 8–11), unnumbered visions (Rev. 12–15), seven plagues (Rev. 15–19), and more unnumbered visions (Rev. 19–22). Visions celebrating the triumph of God occur at the end of each cycle (4:1–11; 7:1–17; 11:15–19; 15:1–4; 19:1–10; 21:1–22:5). Those who read Revelation as a whole encounter visions that alternately threaten and assure them. With increasing intensity the visions at the bottom of the spiral threaten the readers’ sense of security by confronting them with horsemen that represent conquest, violence, hardship, and death; by portents in heaven, earth, and sea; and by seemingly insuperable adversaries who oppose those who worship God and Christ. Nevertheless, each time the clamor of conflict becomes unbearable, readers are transported into the presence of God, the Lamb, and the heavenly chorus. These visions appear at the top of the spiral. Threatening visions and assuring visions function differently, but they serve the same end, which is that readers might continue to trust in God and remain faithful to God.”

I have interwoven Koester’s explanation onto his spiral graphic to show how it works as a general outline. Too often in Revelation, we “can’t see the forest for the trees.” All of the strange details and symbols draw our focus away from the big picture. Therefore, keeping a big picture (or graph in this case) in view can help us follow the main themes and story line. Most of Revelation’s content, themes, and literary structure fit into this outline (although no outline is perfect). Many scholars note Revelation’s visions have patterns of sevens (a number that symbolizes universality or completion) that overlap and repeat earlier material while still advancing towards a finale. Each cycle spirals down into tribulation on the earth followed by a glimpse into heaven to show the sovereign God/Christ moving events towards victory. This patterned presentation, when coupled with frequent Old Testament allusions and symbols, doesn’t just look forward; it looks back to the history of God’s people oppressed and tempted by evil powers. Babylon pursued and persecuted the Israelites of old, and a new Babylon (Rome in John’s day) seeks to destroy and tempt God’s people. The sovereign Lord reigns over all of history; this includes the history of the suffering saints addressed in Revelation’s first three chapters. Yes, there will be eclipses, earthquakes, diseases, and war. God’s people will be persecuted. These patterns were present in Israel’s day, in John’s day, and in our day. However, all these patterns will one day culminate in the final judgment and redemption when Christ returns. Believers don’t know when that day will be; but it is sooner than it was when Revelation was written. The sovereign God of the universe, and the Lamb who was slain for our redemption, directs history. Even when the world is in great upheaval, God’s people have a secure place in Christ. For this reason, Revelation’s call to persevere in the faith is timeless and bigger than the events of our day. At the end of Revelation, Jesus reminds us: “Behold, I am coming soon. Blessed is the one who keeps the words of the prophecy of this book.” (Rev 22:7).

An updated table arranging the New Testament books according to the date of composition.

This blog’s all-time most read post (found here ) contains a table arranging the New Testament (NT) books according to the date they were written. As I have been preparing a NT survey course, I felt the need to slightly update the chart. One such update concerns the Epistle of James. In my first chart, I underestimated the number of conservative scholars who consider James to be the first NT book written. For instance, Carson & Moo’s Introduction to the NT, Dan McCartney’s BECNT commentary, as well as Blomberg & Kamell’s ZECNT commentary suggest that James was written in the mid to late 40s.

The other changes are adjustments to the dates (and therefore their order in the table) that reflect a broader survey in my own reading. Below, I also reproduce the introduction to my original 2018 post.

_______________________________________________________________

Our modern New Testaments are not arranged chronologically, which sometimes causes misunderstandings. While the Gospels discuss the events of Jesus’ life (the crucifixion took place in 30 or 33 A.D.), the earliest Gospel probably was written down about 60. The Apostle Paul wrote many of his letters before the Gospels. This historical perspective is helpful when assessing arguments over material that some scholars may deem a “later theological development” in the early church. For example the “kenotic hymn” of Philippians 2 exhibits a very high view of Christ, despite Paul most likely writing Philippians before the Gospel writers completed their writings. Note the exalted status afforded to Christ:

Have this attitude in yourselves which was also in Christ Jesus, who, although He existed in the form of God, did not regard equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied Himself, taking the form of a bond-servant, and being made in the likeness of men. Being found in appearance as a man, He humbled Himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.

Philippians 2:5-8 (NAU)

Some scholars believe these verses were a pre-existing hymn that Paul incorporated into his letter. If this theory is correct, then the high view of Christ can be traced to an even earlier time. Arguments, therefore, that assume a high view of Christ (i.e. his divinity) always reflects a later church development contain an invalid presupposition.

The table below arranges the NT books by their likely date of composition. Most NT books are difficult to date with precision, which is why discussions about dating can often be lengthy and still not definitive. The dating of the various writings depends on views of authorship, so I have included two columns of dates. The books are listed chronologically, according to their more conservative dating, but the right hand column provides dates from a more skeptical view. Of course, these dates are further debated within their respective “conservative” and “skeptical” camps, but I have tried to give the most common views from my own subjective survey of the data. For the most part, I have disregarded the “outliers” of either camp. I hope readers find the following table helpful.

| Earlier, more conservative dating | NT Book (Listed by date of Composition) | Later, more skeptical dating |

| 45-60 | James | 70-100 |

| 48-Late 50s | Galatians | 50s |

| Early 50s | 1 Thessalonians | Early 50s |

| Early 50s | 2 Thessalonians | Early 50s (later if forged) |

| Mid 50s | 1 Corinthians | Mid 50s |

| Mid 50s | 2 Corinthians | Mid 50s |

| Approximately 57 | Romans | Approximately 57 |

| Early 60s | Philemon | 60s |

| Early 60s | Philippians | 60s |

| Early 60s | Colossians | Early 60s (70-90 if forged) |

| Early 60s | Ephesians | 70-90 |

| Early 60s | 1 Timothy | 90-110 |

| Early 60s | 1 Peter | 70-100 |

| 60s | Gospel of Mark | Late 60s-70s |

| Mid 60s | Titus | 90-110 |

| Mid 60s | 2 Timothy | 90-110 |

| Mid 60s | 2 Peter | 90-110 |

| Late 60s | Hebrews | 60-95 |

| Late 60s | Gospel of Matthew | 80-100 |

| Late 60s-80 | Gospel of Luke | 80-100 |

| Late 60s-80s | Acts | 85-130 |

| 60-80 | Jude | 80-110 |

| 80-90 | Gospel of John | Approximately 100 |

| Early 90s | 1 John | 100-125 |

| Early 90s | 2 John | 100-125 |

| Early 90s | 3 John | 100-125 |

| Late 60s or mid 90s | Revelation | 100-125 |

Wisdom Smarts. Ecclesiastes 1:12-18

If ignorance is bliss, wisdom can sometimes be painful. Often wisdom smarts, it hurts, it makes us say, “I wish you hadn’t told me that.” It is like a confused father trying to figure out why the sink won’t drain, only for his son to announce: “I put marbles in it!” Despite finding the answer, the father thinks, “I wish you hadn’t told me that.” Knowledge often brings grief with it. As we continue our journey through the book of Ecclesiastes the writer of Ecclesiastes observes that adding wisdom usually adds pain. The writer makes this observation in the context of observing and testing out the things of life to see what benefit they have apart from God.

Last post I began this series in the book of Ecclesiastes. For those not familiar with this Old Testament book, it is found right after the book of Proverbs. (Click here for a helpful video overview from the Bible project). Ecclesiastes addresses the human condition with all its limitations and frustrations. Despite Ecclesiastes being a part of the wisdom tradition, the writer expresses the frustration that finding wisdom often means finding sorrow. Today’s post covers Ecclesiastes 1:12-18:

12 I the Preacher have been king over Israel in Jerusalem. 13 And I applied my heart to seek and to search out by wisdom all that is done under heaven. It is an unhappy business that God has given to the children of man to be busy with. 14 I have seen everything that is done under the sun, and behold, all is vanity and a striving after wind.15 What is crooked cannot be made straight, and what is lacking cannot be counted. 16 I said in my heart, “I have acquired great wisdom, surpassing all who were over Jerusalem before me, and my heart has had great experience of wisdom and knowledge.” 17 And I applied my heart to know wisdom and to know madness and folly. I perceived that this also is but a striving after wind.18 For in much wisdom is much vexation, and he who increases knowledge increases sorrow.

Ecclesiastes 1:12-18 (ESV)

In verse 13 the writer tells us about his “life experiment” of observing and testing out the things of life to see what benefit they have apart from God: “I set my mind to seek and explore by wisdom concerning all that has been done under heaven.” In the rest of the book, the writer reports on his findings from this life experiment. He explains what he learned through the wisdom of observation and experimentation concerning life on earth apart from God. His general conclusion, which is repeated throughout the book is in v. 14: “I have seen all the works which have been done under the sun, and behold, all is vanity and striving after wind.” Without God the things of this life are “vanity” (Hevel in Hebrew) and understanding that vanity is the path of wisdom. Hevel/vanity does not refer to “conceit” but to the fleeting quality of life. The things of life are fleeting like vapor or smoke. Previously (1:9) the writer observed that there was nothing really new under the sun. In these verses the writer observes some things about wisdom itself–the very wisdom he is using to observe and experiment on life. He notes in verse 16: “I said to myself, ‘Behold, I have magnified and increased wisdom more than all who were over Jerusalem before me; and my mind has observed a wealth of wisdom and knowledge.‘” The writer got all the wisdom he could. A modern quip is that some drink deeply at the fount of knowledge, but others just gargle. Well, the writer of Ecclesiastes drank deeply.

As a part of the wisdom literature, one would expect Ecclesiastes to say that achieving such wisdom was wonderful. Instead, the writer’s assessment of having attained great wisdom: “I set my mind to know wisdom and to know madness and folly; I realized that this also is striving after wind.” Apart from God, all the wisdom in the world is futile. The writer suggests 3 reasons why.

1) You may know something, but not be able to do anything about it. This problem is alluded to in verse 15: “What is crooked cannot be straightened and what is lacking cannot be counted.” You may know how to count money, but what good does it do, if you don’t have any money to count? You may know all about diseases so you can live longer through prevention, but all that wisdom can not stop the eventuality of death itself. Living wisely is to be preferred, but apart from God all that learning and wisdom ends when you do. Ecclesiastes acknowledges the disconnect between knowing something and actually being able to do something significant with that knowledge. Often times wisdom gives you enough understanding to realize that there are some things you can’t do anything about. This truth is expressed in the famous “serenity prayer”: God grant us the serenity to accept the things we cannot change, the courage to change the things we can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

2)The second reason that wisdom apart from God is futile: true wisdom will teach you that the more you know–the more you don’t know. After being in school of one kind or another for almost 25 years I understand now, better than ever before, that there is so much I don’t know. There is a wisdom in understanding human smallness, and how the world is so much bigger than what our little minds can get around. These limitations should not keep us from trying to figure things out, rather we should realize that just because our minds can’t understand something doesn’t mean it is not true. In fact the more we understand the world, the more we see all the things that are beyond our capacity to know. Even the most wise people in the world are totally ignorant in some things. You can be an expert in nuclear physics but still be clueless about how people work. Without God, this human limitation makes wisdom seem like chasing after wind. I’ll always not know more than I do know. However, when God is involved, not being able to understand everything is reassuring–the world is bigger and more wonderful than my little mind. Without God, the limitation of human knowledge is frustratingly futile.

3) The final reason that the writer gives for the vanity of wisdom is found in verse 18: “Because in much wisdom there is much grief, and increasing knowledge results in increasing pain.” Adding understanding adds pain. As the writer of Ecclesiastes observed life, he discovered the other side of the modern proverb, “Ignorance is bliss.” That proverb is somewhat misleading because that blissful ignorance often is temporary. Despite our ignorance, the reality is still there and eventually it will have to be dealt with. I may be happily driving along ignorant of the fact that my car is slowly leaking oil, but that bliss won’t last too long. The increasing pain from the increasing mechanic’s bill will correspond to my increased wisdom of car care. Then, once I have the wisdom, I now have the responsibility to use that knowledge and check and change the oil. All that responsibility can be a painful choir, so one way or another adding understanding adds pain.

Even in God’s economy, when you increase in wisdom, you increase the pains of responsibility. Those pains can be a blessing when done for love of God and love of people. Conversely those pains can be the weight of a neglected responsibility bearing down upon you. The more privileges and resources we have, the more responsibility we have to use those things wisely. With that blessing of wisdom (or any other thing) is the “grief” of being responsible for that blessing. In Luke 12:48, Jesus said, “From everyone who has been given much, much will be required; and to whom they entrusted much, of him they will ask all the more.” Every person is responsible for what they have. If you have great wisdom, you have a great responsibility- a greater “pain”. James 3:1 points out that those with knowledge will be held accountable for that knowledge: “Let not many of you become teachers, my brethren, knowing that as such we will incur a stricter judgment.”

The added pain of wisdom can be either a negative or a positive. The pain can be on the path to destruction, or the pain may be a “growing pain”. Apart from God, even growing pains ultimately die off, which is why wisdom is described as vanity and chasing after the wind. With God, the added pain of added wisdom can be an avenue of growth. One example of “growing pains” is when we increase understanding of a certain person or situation. That knowledge can increase our own pain. When you enter a hurting person’s world with a real desire to understand them and their situation, you will feel their hurts. You will bear their burdens. As Christians, we have that mandate to bear one another’s burdens, which will increase our own pain.

Of course it is easier to keep people at an arm’s length. Although we won’t understand them or their situation as well, we won’t get hurt either. We know that increased understanding increases our own pain, so we selfishly choose the pain free path – which brings stagnation. As Christians we must accept that increasing wisdom increases pain, but that is the path our Savior took. We are called to this path of pain/wisdom because we are not just working towards a vain understanding and growth that is bound to the earth, but we are striving towards an eternal wisdom that God makes possible. In so doing, we become more like the one who is eternally wise, the one who bore our sorrows and our afflictions and our pains, Jesus Christ.

With God, the increased pain of gaining wisdom is the path of growth and transformation. Without God, the increased pain of wisdom is futility. Like the writer of Ecclesiastes, do we discern that apart from God even wisdom is futile. The more we understand, the more we come face to face with the futility and absurdity of life without God. But don’t let that pain destroy you, let it compel you to seek out God who is the only one who can redeem the futility of life and wisdom. The writer of Ecclesiastes is so painfully blunt because the wisdom of life is a painful truth that we must deal with. But the good news is that the pains of increased wisdom can be growing pains- good pains when God is involved.

Sermons in Ecclesiastes: 1:1-11

Since my pastoral work dominates my time these days, I thought I would depart from the academic content for a time and move into the more practical/devotional. Over the next several posts, I will share a sermon series in the book of Ecclesiastes. For those not familiar with this Old Testament book, it is found right after the book of Proverbs. (Click here for a helpful video overview from the Bible project). As you read along in the biblical text, you will encounter some provocative reading because Ecclesiastes addresses the human condition with all its limitations and frustrations. In light of the recent Covid 19 crisis, the war in Ukraine, and natural disasters, the truths of Ecclesiastes really hit home. Much of life is out of control; life is precarious. In addressing the futility and toil of humanity, Ecclesiastes doesn’t do so with easy platitudes and fluffy religion. Instead of explaining away the frustrations of life, Ecclesiastes states the human condition and shakes us up so that we will live wisely and not just live in a comfortable stupor.

The book of Ecclesiastes holds a special place in my heart because God used it to shake up my life. When I was in college and sailing along in life, the words of this book shook me up, and continued to whisper to me, until I totally reassessed my life.

The book of Ecclesiastes is a part of the “wisdom literature” of the Old Testament. The Wisdom books also include Proverbs and Job. They look at life from a human perspective and how life plays out in this fallen world; they guide readers towards attaining a deep wisdom for living. Much of the wisdom literature is traditionally attributed to King Solomon because of his legacy as being the wisest king of Israel. Ecclesiastes is no different, and verse 1 seems to allude to Solomon: “The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem.” Despite the tradition, the book is technically anonymous since there were many kings who were a “son of David”. Moreover, verse 1 and the last few verses of the book also talk about “the preacher” in the third person. We hear 2 voices in the book, the preacher (maybe Solomon or another person)– who is a critic of simplistic religious formulations, and the author – who interprets the preachers word so that we are pushed toward God and not fatalism.

Read and contemplate Ecclesiastes 1:1-11.

The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem.

(ESV)

2 Vanity of vanities, says the Preacher, vanity of vanities! All is vanity. 3 What does man gain by all the toil at which he toils under the sun? 4 A generation goes, and a generation comes, but the earth remains forever. 5 The sun rises, and the sun goes down, and hastens to the place where it rises. 6 The wind blows to the south and goes around to the north; around and around goes the wind, and on its circuits the wind returns. 7 All streams run to the sea, but the sea is not full; to the place where the streams flow, there they flow again. 8 All things are full of weariness; a man cannot utter it; the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing. 9 What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun. 10 Is there a thing of which it is said, “See, this is new”? It has been already in the ages before us. 11 There is no remembrance of former things, nor will there be any remembrance of later things yet to be among those who come after.

“Vanity of vanities,” says the Preacher, “Vanity of vanities! All is vanity.” This same saying is found in chapter 12 verse 8. It both marks off the teaching of the preacher and proclaims his main message or conclusion. The author then applies that conclusion to urge his listeners to live in the now and seek God. This is good guidance for us in these troubled times when the futility of life presses all around us.

“Vanity” here is not “vain” as in someone who is always looking in the mirror or that person who is so vain that they think this song is about them. “Vanity” here (hevel) can also be translated “Futility”. “Vanity” is one of the key words in this book, so it is important to understand what the writer means. The writer clarifies his meaning through a metaphor he often uses with the word “vanity”: “All is vanity and chasing after the wind.” Chasing after the wind is an absurd mental picture isn’t it? Chasing after the wind/mist/smoke is just chasing air, which you can’t catch it. Wind is just air moving and, in case you haven’t noticed, you already have air in your hand. A dog chasing after its own tail paints a similar picture of foolishness. Why does the dog want to catch its tail, and if it does, what does that change? The tail was attached to its body all along.

In the beginning and the end of Ecclesiastes, the speaker speaks this refrain that emphasizes the precarious nature of life. As we go through the book we will see how the author observed many things about life and came to the conclusion that many of the things that we think are so important are fleeting, that life itself can be futile, and humans are rather small in the grand scope of time. Understanding these things is the path to wisdom.

The 1st observation that the writer makes about life (found in verses 3-11) is that history repeats itself. Life on this earth is the same old, same old, year after year. Verse 5 notes that the Sun rises every morning and sets every evening. The wind blows, then blows some more. Verse 7 adds that the rivers flow into the sea, but the sea never gets filled up, and yet the rivers just keep flowing. Whether we like it or not the earth keeps turning and turning.

In verse 8 the writer moves on to humanity. Just like the earth is the same old same old, so it is with humanity. We are not satisfied when we see something; we want to see more. Our ears are never filled; we always want to hear more. That is what human life on earth is like and always will be.

Things in life, just keep going with no foreseeable end. There is a wearisome repetition to life that reaches towards fulfillment and satisfaction but never seems to arrive. We think the grass is greener on the other side of the fence, but when we get to the other side, we realize that this is nothing new or different. Verses 9-10 add, “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun. Is there a thing of which it is said, ‘See, this is new?’ It has been already in the ages before us.”

This passage of scripture is so relevant to our current cultural climate. We are a people foolishly obsessed with newness and novelty. We always are striving to get the newest and latest thing. If something is new, we assume it must be better. Yet all the fads and trends that are hailed as new, come and go. Just when they are almost forgotten, they come back around again hailing themselves as new. Think of bell-bottom pants or the mullet hair cut as examples. Verse 11 states it well, “There is no remembrance of earlier things; And also of the later things which will occur, There will be for them no remembrance Among those who will come later still.”

When you read history books it is amazing to see the parallels between what happened in the Roman empire and what is happening in America today. History repeats itself because people don’t remember. We think the challenges and issues of our world are so different than at any other time in history, but they are not. Pandemics are not new. There was the Spanish flu of 1918 and the bubonic plagues of the middle ages. The same basic challenges of life existed long ago and will exist again. Every new generation arrogantly thinks they are somehow different, or better, or more challenged, but the continual march of history tends to trample those pretenses. A recognition of this fact leads to wisdom. This is what the writer of Ecclesiastes is driving at in this section of our scripture. Instead of arrogantly thinking that you are the only one to have ever had this problem or solution, instead of thinking that you or the group you are in is somehow extraordinary – Ecclesiastes says, “Not really. In the grand scope of history, it is all rather ordinary.” My son had a t-shirt that summed this up well– “You are unique, just like everyone else.”

Many read Ecclesiastes and think, “Man this book is a bummer. All this talk about life being vain. This section about the same old same old. I just want to curl up into a fetal position and not do anything.” If that your impression of Ecclesiastes, you have missed the point. This scripture is not intended to arrest your development and your life – but deepen your life and make it wiser.

What is the wisdom that we need to incorporate into life, and how do we go about doing that? 1) Newness is not the answer. It is futility to live your life waiting for the next new thing or person to come and change your life, because there is nothing new. Very few things will make much difference in the grand scheme of your life. God- he is eternal, and He is the only one who can make any real eternal difference at all. The only new life available is the new life that God offers through Jesus Christ. Romans 6:4 promises, “Therefore we have been buried with Him through baptism into death, so that as Christ was raised from the dead through the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in newness of life.” Anything other than God passes like a morning vapor.

Some may object and say, “Well things are a lot different now than in Solomon’s day. We have airplanes and television. We have been to outer space, we have all sorts of medicines to cure illness. All of those things have changed life as we know it.” Have they though? Have they solved the deep problems of humanity? This indictment on nothing new does not mean that every little thing is exactly the same, it simply means in the grand scope of time, any new thing is really just a copy of something that has already been around. It means that any improvements are mere window dressing and don’t go to the heart of the matter. We have invented a vaccine for polio, we landed on the moon, we can talk to someone across the globe over the computer, but our short lives still end. Our memories and our accomplishments are forgotten; so has anything really changed that much? We still have the issues of life, relationships, death and eternity. There is nothing new that will solve these issues.

Certainly there are things in life that make a difference for the better or for worse, but when held up against the backdrop of eternity, it shows its own futility. So stop searching for something or someone of this earth to come and transform your life; that thinking is vanity. We think the grass is so much greener and newer on the other side of the fence. So what do we do? Husbands cheat on their wives thinking they just need something new and find out it didn’t solve the inner issue; it changed life for the worse. People purchase the new car or gadget thinking it will change their lives just like the commercials say – but it doesn’t. People spend their lives thinking if only I could do this, or if only I could have that, if only this happened, then I would have a meaningful life. The book of Ecclesiastes slaps such notions aside the head and bellows, “No, there is nothing new under the sun that will give you a life of meaning; it is futility.” What we need is something above the sun, the creator of the sun, of life, of meaning, truth, and real wisdom.

Make the choice today – Stop looking for something under the sun for the answers to life – that is futility. Go to the maker of the sun, the maker of meaning, the maker of all things new. Through Jesus Christ, God will make things new for you – He is the only one able to do that. Will we live in this wisdom that is found only in God, or will we spend our lives vainly seeking out some new answer, which is not really new at all?

The Spirit in John. Part 2 – The Spirit of Truth

In the last post, “The Spirit in John’s Gospel. Part 1,” I discussed how John presented the Holy Spirit, paying close attention to his unique use of the term παρακλητος (sometimes semi-transliterated in English texts as “paraclete”). In today’s post I will examine the Fourth Gospel’s use of the term “The Spirit of truth”. Because John equates παρακλητος with the “Spirit of truth” (John 14:16–17; 15:26; 16:7, 13), one must look at both terms for a full accounting of John’s theology of the Spirit (so go read the previous post if you haven’t) .

Background to the term, “Spirit of truth” in the First-century: “Spirit of truth” appears in several Second Temple texts (Jubilees 25:14; Joseph & Aseneth. 19:11; Testament of Judah 20:1–5; 1QS 3:6–19; 4:18–25). At Qumran, a spirit of truth and a spirit of deceit are at odds within a person (1QS 3:17–19, also T. Jud. 20:1–5). However, this person-centered spirit of truth is not the only sense of the phrase in the Dead Sea Scrolls. The spirit of truth in Qumran carries a different nuance in 1QS 4:18–25. In this passage, the “spirit of truth” parallels the “spirit of holiness” as a cleansing agent in the last days (1QS 4:18–25), overriding the spirit of injustice within a person. In this one scroll then (1 QS), two concepts of “spirit of truth” coexist.[1] While both “spirit of truth”s may ultimately be from God (like all ruah), one is centered in people but the other comes directly from God. In this latter case, Qumran is similar to OT antecedents; the Spirit of truth is the Spirit from God who brings truth (or holiness).[2]

The divine sense for Spirit of truth is found in Joseph & Aseneth 19:11, wherein Joseph kisses Aseneth and gives her the “spirit of life.” He kisses her a second time and gives the “spirit of wisdom,” and then a third kiss gives her the “spirit of truth.” All three kisses seem to indicate giving the Spirit that brings life, wisdom, and truth. Although Joseph is imparting this spirit, it is the Spirit of the Hebrew God as Aseneth converts to Judaism.

John’s Use of the term “Spirit of truth”: From these extra-biblical writings, the “spirit of truth” seems to be a phrase with some flexibility, which makes it difficult to determine dependence. The Fourth Evangelist does not have the anthropologic sense in mind since he clearly links the Spirit of truth with the Paraclete (John 14:16–17; 15:26; 16:7, 13), who is himself identified as the Holy Spirit (John 14:26). The Spirit of truth in John holds the divine sense—the Spirit from God that brings truth.[3] This sense was not necessarily borrowed from Qumran or other texts, but was probably a part of common Jewish religious terminology and language.

By using the phrase “Spirit of truth,” John employs familiar terminology that advances and coheres with his previous presentation of the Spirit. In John’s, “of truth” probably functions as an objective genitive, “the spirit that conveys truth.”[4] In the first half of John’s Gospel, the Spirit is already portrayed as one who manifests the truth of the heavenly realm. As discussed in the previous post, eschatological worship will be “in Spirit and truth” (John 4:24) so that through the Spirit, worship will match the coming heavenly reality. This heavenly reality is itself “truth” that Jesus and the Spirit make available (John 1:17; 8:32; 14:6; 16:13). The Spirit also reveals (makes the truth known) Jesus’ identity to John the Baptist (John 1:33) and reveals the “words of God” to and through Jesus (John 3:34; 6:63).[5] Those who receive these words testify that “God is true” (John 3:33). The portrayal of the Spirit as the “Spirit of truth” builds off these previous concepts, but also leads into John’s more specific treatment of the Spirit/Paraclete in the Farewell Discourse (John 13:31-17:26) .

In the Farewell Discourse, one of the primary functions of the Spirit/Paraclete is to reveal and guide the disciples concerning truth (John 14:26; 15:26; 16:13–15), enabling them to testify to the truth/Jesus (Jesus is said to be the truth in the immediate pretext of 14:6).[6] In this sense, the “Spirit of truth” is similar to Jubilees 25:14, wherein the Spirit of truth is the Spirit of prophecy. The Fourth Evangelist goes further, in that revelation from God is but one gift from the Spirit. The Spirit brings spiritual rebirth (John 3:3–8) and renewed, eternal life (John 4:14; 6:63; 7:38). The Spirit also manifests the true heavenly presence (John 14:16–17). All of the above are Johannine examples of the Spirit manifesting heavenly truths on earth—these truths are more than revealed words.

Johannine pneumatology, therefore, cohesively presents the Spirit as the one who realizes heavenly realities to Jesus’ followers, followers who receive a “pneumatic assimilation to the heavenly realm.”[7] The realization of the heavenly realm on earth accords with eschatological hopes but with shifting imagery and varying terminology. The first half of John’s Gospel uses more cultic imagery to depict Jesus as the realization of the heavenly temple with the Spirit flowing from this messianic center. The second half of John’s Gospel employs more personal imagery and the Spirit’s effect on the post-ascension community. The Spirit (as another paraclete, John 14:16) will continue to manifest Christ’s presence and bring Truth to the disciples. Both halves of the Gospel depict the Spirit’s role in realizing these blessings (whichever image or term is used) to those who believe in Jesus. The various terms for the Holy Spirit: Spirit, Spirit of truth, and παρακλητος all contribute to John’s overall presentation of the Holy Spirit.

End Notes

[1] The various meanings for “spirit” in the same Qumran text parallel John Levison’s findings (The Spirit in First Century Judaism [AGJU 29; Leiden: Brill, 1997], 238–244) for Philo, Josephus, and Pseudo-Philo. In the first century, authors seem comfortable using “spirit” with multiple meanings. As Levison notes, this fact helps explain the Fourth Evangelist’s unannounced shift to Paraclete terminology in the Farewell Discourse. The different presentations of the Spirit cause more difficulty for modern scholars than ancient readers who were accustomed to the flexible use of the term.

[2] While the phrase “spirit of truth” does not appear in the OT, all the elements exist for the Spirit of God to bring the truth of God. For instance, Ps 31:5 and Isa 65:6 refer to “God of truth,” and 2 Sam 7:28 states, “Your words are truth” (see also Ps 43:3; Dan 10:21).The eschatological vision of Zech 8:3 states that Jerusalem will be called “the city of truth.” The truth as a quality of God would naturally be brought by his Spirit. This idea would be similar to the “spirit of wisdom” (Exod 28:3; Deut 34:9), the Spirit who brings wisdom from God. Similarly, Isa 11:2 states, “The Spirit of Yahweh will rest on him, the spirit of wisdom and understanding, the spirit of counsel and strength, the spirit of knowledge and the fear of Yahweh.” All these qualities are brought by the Spirit of God. It is not a stretch for “truth” to be added to these qualities, a development reflected in Jos. Asen. 19:11, the DSS, and John’s Gospel. This divine Spirit of truth concept is shared by John and these other writings because they share a common religious milieu. See James Charlesworth, “A Critical Comparison of the Dualism in 1QS iii,13–iv,26 and the ‘Dualism’ Contained in the Fourth Gospel,” NTS 15 (1969): 389–418, who argues that John may have borrowed some terminology from Qumran but not its theology.

[3] Craig Keener, The Gospel of John. 2 vols. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2003. 2:969–971.

[4] Andreas Köstenberger, A Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009., 395, n. 216; Barclay Newman, “Translating ‘In Spirit and Truth’ and ‘The Spirit of Truth’ in the Gospel of John,” in A Translators Handbook on the Gospel of John. ed. Barclay Newman and Eugene Nida; New York: UBS, 1980. 655.

[5] The revelatory function of the Spirit and word in John is closely connected to the heavenly origin of the Spirit and the word he reveals. This point draws in Porsch’s emphasis on the Spirit’s revelatory function. Felix Porsch, Pneuma und Wort: Ein exegetischer Beitragzur Pneumatologie des Johannesevangeliums. FTS 16; Frankfurt: Knecht, 1974. 404–407.

[6]D. A. Carson, The Gospel According to John. Pillar New Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1991. 500.

[7] David Edward Aune, The Cultic Setting of Realized Eschatology in Early Christianity. NovTSup; Leiden: Brill, 1972, 105.

The Spirit in John’s Gospel. Part 1 -παρακλητος

Studies in Johannine pneumatology gravitate toward the second half of John’s Gospel (a.k.a. “the Book of Glory”). The reason for this focus is that along with the much debated Greek term παρακλητος, John’s presentation of the Spirit becomes more detailed and explicit in the second half of the Gospel. More particularly, the Spirit passages (except John 20:22) are concentrated in the Farewell Discourse.

While the Farewell Discourse contains the clearest descriptions of the Spirit, these passages should not be read in isolation from previous material. “The Book of Signs” (roughly chapters 1-12) develops the Spirit concept (the Spirit marks what is of the heavenly realm and reveals Jesus’ identity) and anticipates the giving of the Spirit (John 1:34; 7:39). These previous concepts feed into the Spirit/Paraclete concept of the Farewell Discourse. Scholars who attempt to understand Johannine pneumatology apart from the Book of Signs, or by simply focusing on the meaning of παρακλητος, neglect the narrative flow of the Fourth Gospel.[1] Such neglect compromises the Fourth Evangelist’s own agenda and presentation. Because the Evangelist explicitly equates παρακλητος with the Holy Spirit (John 14:26), one should assume that the Evangelist wants his readers to understand the Spirit/Paraclete in light of the previous Spirit passages.[2] The presentation of the Spirit certainly undergoes a shift, and understanding that shift elucidates the Evangelist’s agenda.

The Book of Signs presents the Spirit as identifying that which is of the realm of God.[3] The Spirit remains on Jesus (John 1:33) without measure (John 3:34) thus marking Jesus’ messianic identity and heavenly origin. Simultaneously, the narrative looks forward to Jesus giving the Spirit (John 1:33) to anyone who thirsts (John 4:10; 7:37) as a realization of eschatological promises. The Spirit is centered upon Jesus and will flow from him. This forward-looking perspective views Jesus’ glorification as the climatic eschatological hour (John 12:23–27). When the Book of Glory shifts to the hour of Jesus’ glorification, the Spirit theme turns toward Jesus giving the Spirit and what reception of the Spirit means for the disciples. While specific Spirit passages will be analyzed later, some preliminary observations in the Book of Glory show these concerns.